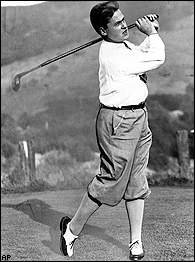

Walter Hagen (1892 - 1969)

Born Rochester, NY of German/Northern Irish stock. His mother, Margaret Daly originated in County Antrim. Hagen is remembered as golf's most flamboyant character; he modernised golf.

Hagen's successes as a golfer which included four Opens, 2 US Opens and 5 US PGA Championships, were overshadowed by his character. He "never wanted to be a millionaire, just to live like one". He was the first golfer to realise the commercial opportunities of product endorsement. Indeed he carried 22 clubs instead of 14 because he was paid US$500 per year for every club he carried. At the height of his popularity, he charged considerable appearance fees for exhibition matches. As a professional at his base in Florida, he charged US$40 per session. In fact, he went on to become the first golfer to earn and spend a million dollars. And spend he did. While staying in London, he hired a Rolls Royce and stayed at the Savoy. The cost for him and party once came to £10,000, the equivalent to a working man's lifetime wage! However he did earn US$100,000 per year during the 1920s.

He popularised colourful clothing on the golf course. Just imagine the sight of this American turning up to play the Open in colourful plus fours and tank top and two-tone shoes, while the rest of the field were wearing sporting clothes with all the colour that brown and grey can afford!

Despite these idiosyncrasies, there was a serious side to Hagen. Back then professionals were considered to be on the bottom rung of the golf pecking order, especially in Britain. They were not allowed to enjoy the facilities of the clubhouse and indeed were sometimes prohibited from entering it through the front door. However golf just mirrored a much wider division of men in society based on class and ancestry. As an American, Hagen had no time for this nonsense. After all, how can it be proper that those who are masters of their craft are considered second rate?

Once to highlight the stupidity of the situation, Hagen hired a Rolls Royce and footman and set himself up outside the clubhouse entrance. He used the Rolls Royce as a changing room given that he was prohibited from entering the clubhouse. On another occasion, he refused to enter a clubhouse to accept his prize because he was refused entry earlier in the day. No one did more to embarrass the golf establishment into elevating professionals to the status which their talents deserve.

Hagen's record of success in the Majors is a testament to his talent as a golfer. He was not one given to exhaustive preparation, mentally, physically or otherwise. As a player, his form was either superb or terrible. Luckily, he was a master of the recovery shot. Hagen was also given to employing psychology in order to exploit any weakness in his opponent. He once called his main competitor out of a clubhouse to watch him sink a putt on the 18th hole. He told him that the next day, he would beat him and win the tournament. Luckily he did.

Hagen's place in golf's hall of fame is deserved not only because of his achievements but also because he brought to the game a much needed sense of sport and fun. Professionals everywhere are indebted to him.

(Additional information supplied by Clare McLorinan ~ nee McCullough, Walter Hagen niece) and her daughter ~ Nuala McKinley)

Francis Ouimet is considered America's First Golf Hero and one of the most important figures in the history of golf. His victory in the 1913 US Open in a stunning playoff upset of Britons Harry Vardon and Ted Ray is viewed as the turning point in American Golf. Ouimet was a relatively unknown 20 year old amateur and former caddie when he tied Vardon and Ray after 72 holes at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts. Ouimet had grown up in a modest home across the street from the 17th green at TCC, and was self-taught, learning to play in his backyard and as a caddie. Prior to his victory, golf was dominated by the British and Scots. There were very few players in America, no public courses, and the game was confined mostly to the wealthy. Ouimet's victory changed all of that. His victory and unlikely background combined to create an inspirational moment. Within ten years the number of players tripled, many new courses were built, including pubic courses, and a line of American golf greats stretching from Bobby Jones to Gene Sarazen and Walter Hagen to Sam Snead and Ben Hogan to Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus to today's Tiger Woods had begun.

Another great moment in golf occurred just before the start of the playoff, when Ouimet turned down the offer of an experienced TCC member who wished to caddie for him, and Francis decided to stay with ten year old Eddie Lowery. The photo of Ouimet and Lowery marching together down the fairway is one of the most famous in golf history, and symbolizes Ouimet's great victory and kindness to a young person. As one of golf's most enduring images, it was selected by the United States Golf Association as the logo for its Centennial celebration.

Ouimet went on to a distinguished amateur golf career. He won the US Amateur in 1914 and 1931 and played on the first eight Walker Cup Teams and was Captain of the next four, compiling an 11-1 team record. He was also revered as a golfing goodwill ambassador, and in 1951 became the first American elected Captain of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews.

Ouimet is one of the most honored players in history. He has been named to every Golf Hall of Fame, and has a room named after him in the USGA Museum. He is also one of only three golfers to have a US Commemorative stamp issued in his name. The 1963 and 1988 US Opens at TCC celebrated the 50th and 75th anniversaries of his dramatic US Open win. The US Senior Open Trophy is also named after him, as are several others. In 1997, The Ouimet Fund began a Francis Ouimet Award for Lifelong Contributions to Golf, and the first three recipients were Arnold Palmer, Gene Sarazen and Ben Crenshaw.

In 1949, a group of Ouimet's friends started the Francis Ouimet Caddie Scholarship Fund. In its first year, The Fund awarded $4,600 to 13 students. Today, The Ouimet Fund is the second largest "caddie" fund in the US and is awarding over $915,000 in 2001-2002. Ouimet described the Caddie Fund as his greatest honor.

.

Bobby Jones was golf's fast study

By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

"All I did was hear Jones, all I did was hear major championships, and from the time I was an amateur, that's what I prepared for," says Jack Nicklaus on ESPN Classic's SportsCentury series.

Bobby Jones was a child prodigy who became The Man.

Bobby Jones won the Grand Slam in 1930 and remains the only golfer to accomplish the feat.

A short-tempered, club-throwing youth he turned into an even-dispositioned and unruffled champion. In the Golden Age of Sport, Jones took his place alongside such giants as Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Red Grange and Bill Tilden. From 1923 to 1929, the Georgia gentleman dominated golf, birdieing his way into this country's heart by winning nine major championships, even though he played sparingly as an amateur. Then in 1930, he won the Grand Slam, which one writer picturesquely called "the impregnable quadrilateral." He was so popular that he was accorded a ticket-tape parade in New York -- before he won the final two legs of the Slam.

First, Jones conquered England, winning the British Amateur and Open. Then he conquered this country, winning the U.S. Open and Amateur. No one else has ever won a Slam (years ago the two major amateur tournaments were replaced by the PGA Championship and the Masters, which Jones helped design).

Adding to the Jones myth was his retirement from competitive golf less than two months after completing the Slam. He was 28.

Starting at 14, Jones spent seven lean years conquering himself. Starting at 21, he spent seven fat years conquering everybody else.

At 14, when he first entered a major tournament, he was considered a sure shot for greatness. When he hadn't achieved it by the ripe old age of 20, many were considering him a failure.

Of this period, Jones said, "I was full of pie, ice cream and inexperience. To me, golf was just a game to beat someone. I didn't know that someone was me."

Robert Tyre Jones Jr. (he was named after his grandfather) was born on March 17, 1902 in Atlanta to well-to-do parents. A sickly child, he was five before he could eat solid food. In an effort to add some robustness to his frail frame, the family moved out next to the fairways of Atlanta's East Lake Country Club.

At six, Jones was swinging a few sawed-off golf clubs. At seven, he was mimicking the swing of Stewart Maiden, the country club pro. "He was never lonesome with a golf club in his hands," Maiden said. "He must have been born with a deep love for the game. He was certainly born with the soul of perfectionist."

At 11, he shot an 80 on the old course at East Lake. His father looked at the card, then his son, and with wet eyes hugged him. At 12, Jones shot 70 and won two club championships. At 14, with high hopes and lots of national press, he played in his first U.S. Amateur, winning two matches before being eliminated.

"Bobby was a short, rotund kid, with the face of an angel and the temper of a timber wolf," Grantland Rice wrote in The Saturday Evening Post in 1940. "At a missed shot, his sunny smile could turn more suddenly into a black storm cloud than the Nazis can grab a country. Even at the age of 14 Bobby could not understand how anyone ever could miss any kind of golf shot."

But for the next seven years, Jones missed many shots and struggled with his temper. His low point came during the third round of the 1921 British Open when, at the 11th green, he committed the unpardonable sin of picking up. He had already taken 50 something shots for the day.

"It was the most inglorious failure of my golfing life," he said some 40 years later.

Finally, at the 1923 U.S. Open at Inwood Country Club in New York, Jones conquered his demons and broke through. But it didn't come easy. He looked like a champion with three holes left, but went bogey-bogey-double bogey, opening the door for Bobby Cruickshank to tie him. "I didn't finish like a champion," Jones said. "I finished like a yellow dog."

In the 18-hole playoff, the two were tied going into the par-four 18th. Both drove into the rough. After Cruickshank laid up, Jones had a decision to make. His ball was 190 yards from the green, resting in loose dirt at the edge of the rough, and water on his next shot was a possibility if he went for the green. Jones liked to describe a dangerous shot that only a golfer with real guts could pull off as a shot that required "sheer delicatessen." Perhaps no shot in his distinguished career was more "sheer delicatessen." With his two-iron, he drilled the ball over the water and to within eight feet of the pin. Two putts later, Jones had won his first major. That two-iron started Jones on his magnificent eight-year run against the best golfers in the world.

While many of his championships were won easily, he almost gave away the 1929 U.S. Open. With six holes to go, Jones led by six strokes. While Al Espinosa played the final six holes in two under par, Jones bogeyed the 12th and triple-bogeyed the 15th. He missed the green on 18 and needed to make a 12-foot putt for a tie. He stroked Calamity Jane, his famous putter, and the ball slowly worked its way toward the hole. It hesitated at the cup, and dropped in.

The next day, Jones won the 36-hole playoff by a whopping 23 strokes, shooting three-under-par 141 to Espinosa's 164.

While Jones' driver and putter were his two best clubs, his best weapon was his will to win. He performed at his best when the pressure was at its peak.

The first stop for the Grand Slam in 1930 was St. Andrews, site of the British Amateur. Of his eight winning matches in the tournament, three were won one-up. That's how close he came to his Slam hopes being slammed in his face at the start.

Some two weeks later, he teed off in the British Open over the links of Hoylake. He won his third British Open in five years, winning by two strokes.

At the U.S. Open at the Interlachen Country Club, in a Minneapolis suburb, Jones appeared to have the tournament won with two holes left. But a double-bogey on the 71st hole cut his lead to one. On the final hole, looking to two putt from 40 feet, he stroked the ball home for birdie and his fourth U.S. Open championship.

He won his fifth U.S. Amateur, which was played at the Merion Cricket Club outside Philadelphia, in a breeze. A bodyguard of Marines protected Jones from his idolatrous fans after he completed the Slam.

"In the clubhouse, after a talk with his father, he began to digest the reality that the Grand Slam was factually behind him and with it the ever-accumulating strain he had carried for months," Herbert Warren Wind wrote. "When he appeared for the presentation ceremonies he looked years younger."

Jones retired with 13 majors, a record that would stand for more than 40 years. "There were no worlds left for him to conquer," Wind wrote.

Jones, who had graduated Georgia Tech and Harvard and was a lawyer in Atlanta, played lots of friendly golf, but he emerged from his retirement only once a year to play in the Masters.

In his last years, Jones was confined to a wheelchair because of syringomyelia, a fluid-filled cavity in the spinal cord that caused him first pain, then loss of feeling and muscle atrophy. The illness became a slow death for Jones, who weighed somewhere between 60 and 90 pounds when he died on Dec. 18, 1971 in Atlanta.

"As a young man, he was able to stand up to just about the best that life can offer, which is not easy," Wind wrote, "and later he stood up with equal grace to just about the worst."